Homiletics Professor Paul Scott Wilson refers to it as “The Tiny Dog.” Specifically he uses as a mnemonic device the phrase “The Tiny Dog Is Now Mine.” TTDINM is meant to help insure sermon unity by asking students/preachers to have One Text, One Theme, One Doctrine, One Image, One Need, and One Mission. The Tiny Dog keeps sermons unified, keeps them from being scattershot.

Jesus in Luke 12 did not get the Tiny Dog memo. Jesus here is rather all over the place thematically and with his imagery. One second we’re hearing about a wedding banquet and being prepped for the arrival of the bridegroom but then before you know it we’ve switched back to the image of a thief entering a house.

If this were a student sermon I was grading . . . well, probably best not to consider grading Jesus!

We begin with words of grace: the Father has already given them the kingdom. And so they have a treasure in heaven that cannot be removed, stolen, or in any way diminished. Good news! Happy days! In these days when anxiety and uncertainty over the stock market keeps people up nights—and in which altogether too many people have seen a lifetime’s worth of savings evaporate overnight—the promise of a portfolio that is rock solid eternally is a mighty delicious promise to savor.

Jesus seems to know this, too. Hence what follows! Make no mistake: the kingdom is ours by grace and it is every bit as secure as Jesus says it is. But our Lord is also wise enough to know that with rock-solid security can come also a sense of entitlement, a sangfroid attitude toward life, maybe even a measure of smugness mixed with laziness.

In other words, what you see in Luke 12 is the classic conundrum of the gospel: salvation by grace alone is great but it can also lead to moral torpor, to the very “Eat, Drink, and Be Merry Because Tomorrow We’re Forgiven Anyway” attitude that the Apostle Paul dealt with in the very earliest days of the church (cf. Romans 6). Or to invoke a phrase attributed to the German philosopher Heinrich Heine, “God likes to forgive. I like to sin. Really, the world is admirably arranged.”

It goes without saying that such an attitude cannot characterize disciples. And so Jesus goes right on to offer some words designed to provide moral seriousness and preparedness for Christian disciples. Yes, the kingdom is a free gift and it’s secure forever. But nevertheless, be watchful, be mindful, be ready for the Lord’s return at any moment because only such a posture of devotion and readiness displays the kind of grateful heart that it is only fitting for people who have received such a great gift to have.

I think we all understand this. Who among us does not love to lavish things on our children: good food, fun gifts, family vacations to beautiful locales. We love giving this to our kids even as we hope they know that our love for them as parents is rock-solid, secure, unassailable. But even so, what parents wants to see those kids grow up to be spoiled brats? Who wants a rude and entitled child who begins every sentence with the words, “I want . . .”?

We want to achieve that tricky balance between unconditional love and a grateful loving response in return. We want to give them the world but not allow them to think the world is their oyster to do with as they please. We want, in short, to be loved as we have loved, to be generous in ways that in turn produce generous children who will spread that same goodness around to their children and to the other people in their lives. We want to create good moral momentum.

And so does Jesus.

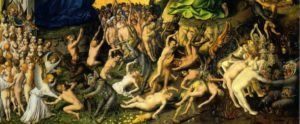

But is there a way to proclaim the parousia, the return of Christ, in a way that is not threatening? We all know that in history the prospect of Christ’s return—and the subsequent “Judgment Day” that this will usher in—have been used by the church as a bludgeon, as a rolled-up newspaper raised over people’s heads in ways designed to make them behave. The return of the master of which Jesus speaks in Luke 12 has been a moral wedge, a fundraising tool, a nightmare. Artwork depicting Judgment Day tends to be a little on the scary side.

Of course, if Jesus really is coming back and if we are to proclaim this as a church, then there is no way we cannot tell people that it is coming and that what this means is that history has a purpose, an end point, and there will come a time of reckoning when what is wrong with life will get corrected. And I suppose that if you are not a believer in Jesus, then none of this talk will mean much to you. However, deep in the unbeliever’s heart will be the secret, albeit unacknowledged, truth that if that really happens, such an event could well spell bad news for all those who did not live for Christ.

In Luke 12, in the verse that comes just after the Lectionary cuts off this reading (verse 41), Peter asks Jesus who his audience is. “Lord, are you talking to just us insiders or to the general hoi polloi out there?” Jesus seems to indicate in his answer that he’s talking to just the disciples. But the larger crowds no doubt heard it, too.

So here is my question: what is the best way to talk about the return of the master both inside the church and outside the church? It’s a vital question because I think we have tended to mess up this message in both settings. And the reason we have messed it up is the same in both venues: we forget that the starting (and so ending) point of the gospel is love fueled by grace. In Luke 12 Jesus first tells the disciples that they are all set, that the kingdom is theirs, that they are eternally secure. True and as noted in another section of this set of sermon commentaries, that was not meant to induce laziness or a morally lax attitude. Watchfulness and faithfulness were still called for. But if we keep the up-front message of grace prominent, then we will find it all-but impossible to turn the prospect of Jesus’ return into a moral bludgeon with which to frighten believers into submission.

If it’s true that perfect love casts out fear, it’s also true that fear-mongering short-circuits love. It’s also a grace killer every time.

But what about for those outside the church and outside the faith? Surely it’s not wrong to hold up the return of the master as a source of fear to them. After all, they have a reason to fear, don’t they?

Well, perhaps. Let’s not pretend that the prospect of judgment is something to be taken lightly. And let’s not forget that no figure in the New Testament spoke about that final reckoning—as well as the prospect of hell—more than Jesus himself.

Nevertheless, if the gospel is truly Good News, if it is truly a proclamation of love fueled by grace, then frightening people into the faith is almost certainly the wrong way to go. Because the master who returns in the end will be the same loving and gracious Lord who died in our place and who, in his life prior to that sacrifice, exuded nothing but love and kindness to especially those in society whom the religious folks of the day deemed the least worthy of such grace.

We’ll never make people fall in love with that gracious Savior if all we do is scare them to death with the prospect of meeting him. If we want to keep in mind the prospect of final judgment, then let’s use that as the motivation to reach out to all people with the gospel of grace. But let’s begin with the love. It may well be the best chance we have to be used by the Holy Spirit to head off a fearful conclusion.

Illustration Idea

Some years ago I had the privilege of hearing Barbara Brown Taylor deliver a sermon at the Princeton University Chapel. At one point she related a story from her childhood when she was growing up in the American South. Every day after school Barbara and her siblings were supervised by an African-American babysitter named Thelma. Thelma was remarkable for how little she ever talked to the children. Each afternoon she’d sit in a rocking chair reading her Bible while the children did homework or played. If things got out of hand, all Thelma had to do was lower the Bible an inch or two, just enough for the children to see her eyes glaring overtop the old King James Version, and order would be rather quickly restored.

One afternoon, to the children’s surprise, Thelma engaged them with an activity. She told them to go fetch some blank sheets of paper and crayons. She then instructed them to draw their house: a classic southern home replete with a big pillared front porch, a nice lawn with some oak trees, and even a white picket fence. And so the children drew the house even as Thelma encouraged them to include as many details as they could. When the kids had finished their portraits, Thelma then said, “Now, I want you to draw fire comin’ down from the sky. Draw the fire lickin’ up the oak trees and the picket fence and the roof. Draw it that way ’cause that’s what’s gonna happen when da Lord comes back.”

Well this widened their eyes a bit. But what has stuck with Rev. Taylor in the years since then was not just that Thelma gave the children a backdoor eschatology lesson but that for Thelma this future fire was something to look forward to. Barbara and her siblings were too young and naive to appreciate the racial tensions in the midst of which they lived. They did not see their living in a nice house as something that might cause resentment on the part of black people whose opportunities for a similar lifestyle were, at best, minimal. A fire of judgment which would one day by and by set all wrongs to right looked good to Thelma. But it felt like a threat to Barbara and the other kids. What looked like a new beginning to Thelma looked like the end of everything to the children.

Sign Up for Our Newsletter!

Insights on preaching and sermon ideas, straight to your inbox. Delivered Weekly!

Sermon Commentary for Sunday, August 11, 2019

Luke 12:32-40 Commentary