Most scholars seem pretty certain that Psalms 42 and 43 were either originally just one psalm or that they are such tight companion psalms that you are not really supposed to read either of them in isolation from the other. But here we are being asked to look at only Psalm 43. A glance back to the previous psalm shows that the themes of these two poems are identical. This is the Hebrew Psalter in full-on lament mode, which is true of basically one-third of all the 150 Psalms.

Psalm 42 begins with the plaintive image of a deer suffering from dehydration and literally panting for streams of water. This, the psalmist claims, is his soul and its disposition toward being able to locate God in a time when God appears to have gone off duty. Like all the Psalms of Lament, the irony here is that the psalmist is lamenting the apparent absence of God but he’s doing it in a prayer TO GOD even so! The psalmists apparently saw no inherent contradiction in expressing frustration over God’s absence and saying so to God’s face.

One element in Psalm 42 that is not per se repeated in Psalm 43 is the taunting jeers of the psalmist’s critics. The psalmist is not the only one who is aware that he feels God has gone silent. His enemies and naysayers know about this too and they use it to taunt him. “Where is your God, pal? How come he’s not coming through for you? Why is he not listening to you?” One can only conclude that these people are not believers in God. They are cynics, agnostics, and if they are not atheists, then perhaps they believe in some god other than the Yahweh of Israel. In any event, pouncing on someone who is having a crisis of faith could only be the action of someone who all along had found this person’s faith specious or ridiculous.

What both psalms share in common, however, is the effort to remember past times when God came through as a goad to nurture hope that one of these days that will happen again. In Psalm 42 some specific references to apparently past events are listed in this vein. And the clearest linkage of these two psalms is in the refrain that comes in Psalm 42:5, 42:11, and 43:5.

Why, my soul, are you downcast?

Why so disturbed within me?

Put your hope in God,

for I will yet praise him,

my Savior and my God.

These words are familiar enough to many of us that we maybe never step back to observe how curious it is that the psalmist addresses his own soul almost as though it were a separate entity from himself. It’s like some serious self-talk except in this case he seems less to be talking to himself (sort of along the lines of saying to myself, “Come on, Scott, get with the program here!”) as he is talking to a portion of himself and telling it to buck up. It is a little bit of an odd way to frame things.

In any event, Psalms 42 and 43 share in common a trait that is in most all of the Psalms of Lament: confidence that the bad season he is passing through will not last forever. He is strangely confident that God absolutely will come through for him, will vindicate him before his public detractors, will flat out show up in his life again. And that confidence is then the foundation on which the psalmist further builds his promise that when all of that happens, he will give God the praise and the glory for it.

Is this a subtle way of bargaining with God? “You do this, O God, and in return you will again get my praise instead of the lament I am uttering right now.” Tit for tat? Quid pro quo? Maybe. Or it could be a little of that but also a sign that even in the modality of full-throated lament, the psalmist is devoted to God, loves God, and is actually eager to have reason to join the festive throng in going into a worship service again.

The Psalms of Lament teach us several things, not the least of which is that praying this way is not a sign of weak faith but robust faith. Laments are not uttered by non-believers or skeptics. This is how people of faith can pray when it is needed. God is not offended by our laments. He can take it when we tell him we feel disappointed in him, distant from him, maybe even when we are a bit angry with God.

We shy away from this today. Nearly 50 out of the 150 psalms are in some fashion laments and yet in worship today, most churches focus on only the praise psalms. As a colleague said to me years ago, many churches now have a “Praise Team” but no one has a “Lament Team.” Few acknowledge in the context of worship that not everyone is as brimming with praise on a given Sunday morning as the Praise Team seems to signal we all ought to be. In seasons of lament, praise sticks in our throats. And the Psalms of Lament seem to say that this is okay with God, too.

But if there is even remotely anything to the tit-for-tat, quid-pro-quo nature to some of this as just observed, then this too is instructive. No, we ought not base our relationship with Almighty God on some contractual deal where we will keep praising God if and only if he consistently comes through for us. Otherwise all bets are off! No. At the same time, however, there is nothing wrong with hoping—even expecting—that God wants the best for us and so we have reason to ask for such things without feeling the least bit entitled in doing so.

But even as we shy away from lament in public worship sometimes, so also our posture in prayer is very often as dutiful and submissive servants who don’t deserve a blessed thing from God and so even when bad things come our way, we think we ought not complain and in fact just suck it up as character formation or some such. We certainly would feel impudent in suggesting to God he owes us one now. The psalmists do not always evince such a passive posture.

Psalms like the 42nd and 43rd psalms do not always sound like the prayers we often utter. Maybe these poems are in God’s Word to suggest that such prayers are just fine.

Illustration Idea

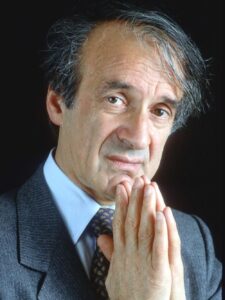

Nearly thirty years ago at the Festival of Faith & Writing at Calvin College (now University), Holocaust survivor and brilliant writer Elie Wiesel gave a memorable plenary address to a packed Fieldhouse. At one point he told a story that illustrated what he meant in the speech when, speaking of the Psalms of Lament, he said that “A Jew can be for God, happy with God, against God, angry with God but a Jew can never be without God.”

It seems that in one of the Nazi concentration camps a number of imprisoned Jews decided to put God on trial for covenant unfaithfulness given the suffering of his people in those dark days. They asked a rabbi who was also in the camp to preside as judge. Testimony was given, cross examinations happened, and in the end the verdict came in on the charge of God’s covenant unfaithfulness: Guilty as Charged. They were about to announce the sentence but they had to break off before they got to that part.

It was, you see, time for evening prayers.

Sign Up for Our Newsletter!

Insights on preaching and sermon ideas, straight to your inbox. Delivered Weekly!

Sermon Commentary for Sunday, November 5, 2023

Psalm 43 Commentary