Whenever I read Psalm 126, the phrase “delirious with joy” leaps to mind. What emerges in the opening verses here is a portrait of people whose wildest dreams somehow came true and they discover that they just cannot stop giggling over it and grinning like the proverbial Cheshire cat over and over and anon. Weeping has been replaced with joy. Sorrow has been supplanted with singing. Scarcity has given way to people joyfully carrying abundant sheaves of wheat with them.

Historically it’s a little hard to place this poem. If the return from exile is in view here—and that seems likely—then we know that the actual return to Jerusalem was a rather difficult and fraught phenomenon. Challenges abounded for those trying to restore Zion and in truth, they never quite achieved it fully. Or at least not for centuries. Nehemiah and Ezra narrate a good bit of this story for us. At one point—far from this picture of people laughing and singing and smiling—when the people who could remember the former glory of Solomon’s Temple look at what little of that they had thus far managed to rebuild, they start to weep at the disparity between what had been and what was currently their lot.

So perhaps this psalm is as much aspirational as reflective of what really had gone on. The joy of the return was real. The realizing of their dreams for release from Babylonian captivity was actual. But maybe as portraits go, this one got a little idealized.

But for this commentary I want to pick up on something else in Psalm 126. It is actually something you see a lot in the psalms, though I think we often breeze past it without lingering on it or wondering why this was so important to Israel. What I mean is the line in verse 2b about how it was said among the nations “The Lord has done great things for them.” Again, you pick up on this idea a lot in the psalms. It seems important to the Israelites that other people see their joy, see their salvation, see their restoration and find in it a cause to marvel and maybe even to exclaim over the mighty acts of Israel’s God, Yahweh.

Why was this so important to the Israelites? And was it ever literally true that other nations took note of Yahweh and praised that God’s good works? Maybe and maybe not. We cannot know for sure how often this happened. Yet it appears that the people of God wanted to be noticed. They wanted to stand as a witness to their great God. In many psalms in what I have labeled “the praise imperative,” the Hebrew phrase hallelu yah is used as a command to other kings and nations to join Israel’s choir in singing praises not to some generic deity but specifically to Yahweh. That probably did not go over real big among those other nations any more than it would go over big today to ask Muslims or Hindus or people of no religion in particular (the Nones as they are now called) to sing a song to Jesus.

But it is interesting to consider that Israel wanted to be seen among the nations. They wanted their God to be seen in a positive light. One wonders among the members of the New Israel that just is the Church of Jesus Christ our Lord if we have any desires similar to this. Do we ponder how the wider world regards God’s people? Is it important to us that people find a cause perhaps to marvel over what our Lord has done for us? Are we conscious of a wish to be seen in a positive light even by people who may not share our faith? Should this be a wish or desire for us?

It actually seems like we don’t often think this way about our congregations and how they may be regarded in the wider communities or societies of which we are a part. And in fact in recent times—as the culture wars have crept into the church and as many Christians are now perceived as embodying a particular stripe of highly partisan politics—if anything what “the nations” see in the church are primarily negative things. Some find the church to be deplorable.

It reminds me of the famous line of Adlai Stephenson in the 1950s when he ran for President (twice) against Dwight D. Eisenhower. Someone asked Stephenson what he thought of the positive preaching of Norman Vincent Peale and his self-help version of Christianity. Stephenson replied with his usual keen wit, “I find Paul appealing and Peale appalling.” Or it reminds me of a line from a poem I once read in which some non-believing parents are trying to deal with a child who loves Vacation Bible School at their local church. At one point the parent says she cannot bring herself to tell her child that the Bible is a book some people use to make other people feel sad.

Now to be clear, the Gospel carries its own offense with it to those who reject it. Last week we noted from Psalm 85 that the Advent Season itself carries with it a need for penance and confession of sin. And not a few people don’t like being told they need to repent. But what about those times when the offense is not the Gospel but the people who claim to embody that Gospel? Should it be a concern for us that when people peer into church communities they often do not find good reason to exclaim positively “The Lord has done great things for them!”?

Advent and Christmas are a time perhaps when people who sometimes do not darken the doors of churches very often attend a service or two. Or at least this is a season when even people who don’t think about Jesus a lot cannot escape the muzak from the speakers at the mall that play “O Little Town of Bethlehem” or “Joy to the World.” And so perhaps those of us who love Jesus and do worship him on a regular basis can have a care about what the watching world thinks of us and of our witness to Christ. Here is hoping and praying that the day may come when more often than not people can look at the church and see people genuinely delirious with the joy of Psalm 126. And maybe if they do perceive that, they may find a hankering somewhere deep in their hearts to get in on some of that holy joy themselves.

[Check out our special Advent and Christmas Resources page for even more preaching and worship ideas, sample sermons, and more for Advent 2023.]

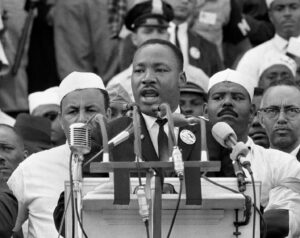

He didn’t make it up on the spot. It was part of a sermon or a speech—and with Martin Luther King, Jr., there sometimes was not a lot of difference between the two—that he had delivered before and that colleagues had heard. But he was not necessarily planning on using those words that day at the Lincoln Memorial with huge throngs of Civil Rights supporters arrayed before him on the National Mall. But after he had been speaking for a bit, some of King’s colleagues behind him began to say, “Tell them about the dream, Martin. Tell them about the dream.”

And that’s when he said it. That is when he began some of the most famous words in the whole history of oratory. “I have a dream” King said. And in the coming minutes as he spooled out what that dream looked like, it somehow felt less like a dream and more like an achievable reality after all. You could see it. You could hear it. You could feel it. And when King capped what is now known the world over as his “I Have a Dream” speech, when he said that the words of the old Negro spiritual would soon come true: “Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty we are free at last”—well, just hearing him end the dream like that made everyone who heard him feel a bit more free already.

Dreams can do that. Yes, we all wish this dream could be fulfilled in all the ways King imagined and articulated. We don’t quite get the Psalm 126 picture yet of people whose mouths are filled with laughter because a dream had come true. But keeping the dream alive is still so vital. For the day will come, in God’s in-breaking kingdom, when this will be everyone’s reality.

Sign Up for Our Newsletter!

Insights on preaching and sermon ideas, straight to your inbox. Delivered Weekly!

Sermon Commentary for Sunday, December 17, 2023

Psalm 126 Commentary