Even allowing for poetic license, it is a little difficult to know what to do with Psalm 51:6. Despite in the previous verse having referenced what we often call the doctrine of Original Sin—we are sinful from the get-go and thus not only after we commit an actual sin—in verse 6 the claim is made that God desired faithfulness from the psalmist even while he was in the womb. And you’re not done trying to figure out just what intrauterine faithfulness would look like when yet another startling claim is asserted: God taught the psalmist wisdom in there too.

Unlike everyone who had ever lived prior to the 20th century, we now have a good idea of what life in the womb looks like. Ultrasounds and other imaging technology that have only recently been developed allow parents to see their unborn child. A live ultrasound shows the fetus moving around, even sucking its thumb, and the grainy black-and-white static image the expecting parents go home with quickly gets posted to Facebook and shown to anyone they run into. All in all, however, life in the womb hardly looks like a classroom! The fetus is developing in many, many ways for certain—it’s a miraculous nine months—but growth in divine wisdom is not on the fetal development checklist. Look at the index in the widely used book What to Expect When You’re Expecting and “wisdom” won’t be in there.

But Psalm 51 is poetry so we know better than to take all of it literally. So what can we do with verse 6? Perhaps we can see this as an indication of something else connected to Original Sin; viz., even as infants we are not supposed to be steeped in sin. Whatever faithfulness in the womb would entail, it would not involve that baked-in proclivity to be sinful. However much of God’s wisdom an infant might be expected to possess, what should be there is the original goodness of a creation unsullied by a fallen human nature. Bearing children who already bear the marks of Original Sin—guilt and corruption being its two prongs—is, in the words from the title of one of Neal Plantinga’s books, not the way it’s supposed to be.

There are a number of poems and songs in the Hebrew Psalter that are in the category of Psalms of Confession but Psalm 51 has long stood out as the most well-known of them all. Something about the plaintive pleas for forgiveness feels apt and applicable to us all. Although the superscription claims both that David wrote this and that the occasion was the aftermath of his adulterous affair with Bathsheba and the de facto murdering of her husband Uriah, we don’t know for certain who wrote this or what occasioned it.

What we do know for certain is that every spiritually honest person admits that sooner or later and far more often than we wish were the case, something in our own lives occasion the need for these words. If there are lines from other psalms that seem a bit foreign to us and are words we would be somewhat unlikely ever to include in one of our own prayers, the lines, “Have mercy on me, O God, cleanse me from my sin” are not foreign to us at all. We have prayed these words. We need these words. And we need the forgiveness and renewal sought by this psalmist.

Probably those of us who were raised to include saying sorry to God in our prayers cannot fully appreciate how foreign this may be to some people and also how and why some would resist doing this at all. Many fancy themselves as pretty good people. Sure, we all make mistakes and now and again we mess up big time. But some regard the language of Psalm 51 as reflective of something rather neurotic. It strikes some as strange to be so hung up with all this sin talk. But far from being a neurotic hangup, the routine confession of our sinfulness is reflective instead of how much we love our God in Christ and how much we love the world for which Jesus died. We pine to have within us the mind of Christ—which is a New Testament way of saying what the psalmist wrote in verse 10 about creating a pure heart in us and placing a steadfast spirit within us.

Psalm 51 is a frank admission of our human sinfulness. But it also contains eruptions of great joy. Apparently as it turns out, those two things actually do go together.

Illustration Idea

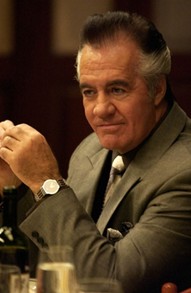

In a scene from the violent and profane mafia TV series The Sopranos, the character who goes by the nickname Paulie “Walnuts” admits one day to one of his many partners in crime that he knows he’s done a lot of bad things. And indeed as viewers we know this. The least of Paulie’s problems are that he is profane while at the same time being a bit of a dandy who in his vanity always wants to be dressed impeccably with his hair coiffed just so. He’s sexually loose, having sex with most any woman who catches his fancy. But he is also a mostly remorseless killer. On the orders of his boss Tony, Paulie would shoot anyone who betrayed them or posed some other threat and having emptied his pistol into the chest of someone, Paulie would shrug and walk away as though he’d just done no more than put his garbage can by the curb.

So yes, Paulie is a bad man who has done bad things. But then he tells his associate that the way he sees it, God will put him in purgatory for a duly long while but then having been purged of all this life’s evils, voila, he’ll spend eternity in heaven after all. But you would not call Paulie’s words a confession of sin by any means and he’s surely not confessing anything to God. And he most assuredly is not, a la Psalm 51, asking God to put a right spirit within him going forward so he won’t keep doing rotten and evil things. (And anyway even those who believe in the existence of purgatory don’t see it as the inevitable place to which anyone might be sent—God has another option that is not, as it were, temporary.)

Paulie may be an extreme example and a fictional one at that but in truth there are lots of people in this world who pass their days if not most of their lives with nary a thought to whatever sins they may have ever committed. Be it something relatively minor like losing your temper in a slow supermarket checkout lane or more serious like committing adultery or defrauding someone, many people never feel motivated to be penitent about such things or about anything at all. But Psalm 51 stands as testament to the grim truth that we all should confess our sins to God and regularly at that. It is a key way by which we acknowledge that life as it is does not reflect life as it should be in a creation God once called “very good.” And such penitence before the face of God is the only hope we have for any modest improvements in our own lives and hence in the wider world.

Confession is a key place along the way that leads to shalom.

Sign Up for Our Newsletter!

Insights on preaching and sermon ideas, straight to your inbox. Delivered Weekly!

Sermon Commentary for Sunday, September 14, 2025

Psalm 51:1-10 Commentary