I come from an ecclesiastical tradition that for a long time shunned the singing of anything but settings of the 150 psalms in worship. Despite a burst of hymnody in the post-Reformation church world—think of names like Isaac Watt or the Wesleys—singing any text that was not straight out of the Psalter was verboten. Ironically some of those very psalms—including prominently Psalm 98—urged the people of God to sing “a new song.” So it would seem that some of the very psalms that my tradition once said were the only approved texts for communal singing pointed beyond themselves to an ongoing process of finding new tunes and new lyrics with which to praise God.

Perhaps that is why when I grew up, my denomination had long since expanded its musical repertoire for worship and so the first songbook I can recall using in church was not just “The Psalter” but instead “The Psalter Hymnal.” And in recent years we have seen the rise of many gifted songwriters: the Gettys, Wendall Kimborough, Marty Haugen, Kirk Franklin, Chris Tomlin, et al. We continue to sing the Lord new songs.

Perhaps it is also possible that the psalmist who penned Psalm 98 was referring to this very psalm itself as being, at the time anyway, a new song. Everything was new at some point. In any event, once we are encouraged to sing new songs to the Lord, Psalm 98 then takes off and launches into ever higher heights of glorious exuberance and even hyperbole. It is one thing to remind Israel of God’s faithfulness to them and of the salvation that God wrought before their very eyes. But Israel alone is far too limited a scope for this psalmist. He needs to declare that this salvation has been made known to all the earth. Everybody. Every nation. Every people.

Well, it is possible that something like the story of Israel’s exodus from Egypt had gotten some air time in other nations. Certainly Egypt did not forget it. And we know that by the time Israel started to enter Canaan and particularly the city of Jericho, people like Rahab made it clear that other people had indeed heard about the God of Israel. But it has to count as a kind of superlative to claim every nation and tribe and person knew all about it. But the idea behind the exaggeration is that this is a God and this is a salvation so wonderful, they deserve to be known by the entire planet.

And if it were so globally if not galactically known, then the whole planet would join in the praise chorus to Israel’s almighty and gracious God. All the people are summoned to join the choir. The very ends of the earth need to get in on the joy of it all, on the music of it all, of the singing and the shouting of it all. Here in Psalm 98 is a portrait of exuberant worship that knows no bounds it seems.

If you don’t believe that claim, then notice how as Psalm 98 moves on, the psalmist makes a move that can be observed all over the Hebrew Psalter: he enjoins the non-human creation to be a part of the choir as well. The seas, the rivers, the mountains are all told to use whatever they have at their disposal to also worship the Creator and Redeemer God of Israel. The imagery here grows in exuberance and rises ever higher until near the end of Psalm 98 we are taking in a riot of praise, deafening in its volume, breathtaking in its scope.

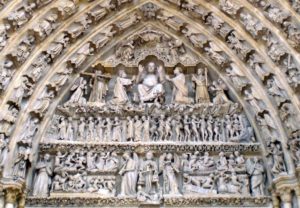

But then comes the somewhat surprising conclusion to it all: this God is coming to judge all the earth. To some people then and now, that might seem to be a prospect that might just take the air out of the celebration Psalm 98 has been building up to. Judgment, after all, could be something to be feared. The words “Judgment Day” don’t typically bring a smile to most people’s faces. Even the church across the ages has at times used the prospect of Final Judgment to sober people up. A lot of European cathedrals have fierce scenes of judgment above the main entrance into the building, almost as a way to say to people that this is serious business so before you enter the church, you’d best shape up and listen up and learn to behave. Or else!

But in Psalm 98 this is not an attempt to alarm people but is the final exclamation point on all the praise the rest of the song had been summoning from the whole earth. The reason this prospect of God’s coming in judgment adds to—and does not subtract from—all of the prior singing in this psalm is because of the character of the God who will do the judging. The judgment in question comes from a God full of righteousness and it is from that deep well of holiness and goodness and righteousness that God will do the judging. And this righteous God is therefore a God of equity as well. Although Psalm 98 does not note this—but many other psalms do—for now in this world the books of justice do not always seem to balance out. In fact, sometimes it feels as though they seldom do.

For this reason the idea that there is a good and righteous God who will sort this all out in the end is good news indeed. Because all of the salvation that the rest of Psalm 98 celebrates with such excitement would mean nothing if in the end that salvation were not completed in ways to make sure that all the wrongs of history will be righted. A few years ago Barbara Brown Taylor wrote a book titled Speaking of Sin and one of the chapters had the paradoxical title of “Sin Is Our Only Hope.” Obviously what she meant was that we have to hope there is such a thing as sin because that means that there is also a cosmic norm from which sin is therefore a deviation. Sin is not the norm. Righteousness is. Similarly Psalm 98 could well claim that “Judgment is our only hope.” Because that means that in the end Israel’s wonderful God—and we now believe our God in Christ—will be all in all and that the righteousness that our God and Savior embody so perfectly will no longer be something we pine for or aspire to. It will be our world.

And that elicits a riot of praise for sure.

[Note: In addition to our weekly Lectionary-based commentaries we now have a special Year A 2025 section of additional Advent and Christmas resources that we are pleased to provide. Please check them out!]

Illustration Idea

The Medieval Church did a pretty good job of using the prospect of hell and final judgment as a bludgeon to keep people in line but also as an incentive to raise money. The Catholic Church sold indulgences as a way to get oneself or one’s loved ones out of purgatory sooner rather than later. Famously, a German preacher and theologian named Johann Tetzel was particularly skilled in bilking money from people and is said to have used the slogan “Whenever a coin in the coffer rings, a soul from purgatory springs.” Tetzel died in 1519, just two years after Martin Luther sparked the Protestant Reformation and a return to salvation by grace alone through faith alone and not through good works (and definitely not through financial contributions to Rome).

Nearly 45 years after Tetzel’s death, the Calvinist wing of the Reformation published “The Heidelberg Catechism” and it clearly took aim to address some of the excesses of the Medieval Church. The Catechism famously opens with the question “What is your only comfort in life and in death?” But such comfort becomes a touchstone throughout the confession, even when picking up on a key article from the Apostles’ Creed. When the Catechism authors got to the line “He will return to judge the living and the dead,” they asked “How does Christ’s return to judge the living and the dead comfort you?” Not only was framing judgment as a source of comfort in direct counterpoint to how the Roman Church and others had been talking about it, it lines up quite nicely with how Psalm 98 clearly views this matter as well.

Dive Deeper

This Week:

Spark Inspiration:

Sign Up for Our Newsletter!

Insights on preaching and sermon ideas, straight to your inbox. Delivered Weekly!

Sermon Commentary for Sunday, November 16, 2025

Psalm 98 Commentary