Babette’s Feast (1987). Written by Karen Blixen (short story) and Gabriel Axel (screenplay). Directed by Gabriel Axel. Starring Stéphane Audran, Bodil Kjer, Bergitte Federspiel, Jarl Kulle, and Jean-Philippe Lafont. Music: Per Nørgaard. Cinematography: Henning Kristiansen. Rated G; 102 mins. Rotten Tomatoes 100%

Babette’s Feast is a film of many wonders—social, aesthetic (cuisine), narrative, cinematic, and religious—and they all intertwine, a skein of surprise and deeply significant meaning. One of the most curious of these is historical, specifically the curious turns of events that propel the startling revelatory events of the film’s conclusion. So much so that this tale invariably brings thoughts of what we used to call Providence, meaning a divine arrangement or direction of events to bring about, broadly speaking, benefit to some and destruction to others. The degree and kind of divine management is a terribly thorny topic, for some see a divine hand in the most trivial events of daily life and other devout people yearn for the slightest revelatory twitch from a loving divine will. The Bible itself complicates these vexing matters. After all there is Job, Jonah, David, and so on, none of whom have a happy time of things. And many of the early followers of Jesus come to a horrific end, from James to Paul, not to mention Jesus himself, who dies forlorn and alone, hurling his fate back at God the Father, at the end hoping for the best (“Into thy hands…”). Hardly anything gets more personal as we search past and present for shards of evidence of divine care in individual fate. And then there’s the familiar counsel that God’s providential presence, if such exists, is best seen in a rearview mirror. Maybe so. Maybe. Whatever.

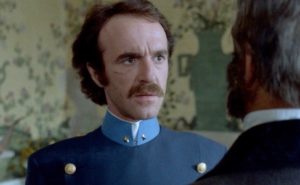

In Babette’s Feast, riddles of this sort abound. Early on, the young sisters, daughters of the founder of a tiny Lutheran pietist sect, seemed fated to solitary lives due to their father’s disapproval and intervention in their romantic options. One is pursued by a dissolute young officer, Lorens Löwenhielm, who has cleaned up his act now that he has found love. The other, with the voice of an angel, is adored by a celebrated French opera singer, Achille Papin, who by chance hears her singing when he wanders into a rural church to rest during his sojourn in the countryside.

The departure of both seems a cruel turn, and the sisters thereafter spend solitary faithful lives on the rural Danish seaside, tending the dwindling remnants of their father’s flock.

And then, and then, decades later, in 1871, to be precise, along comes a cook, one Babette Hersant, a refugee from mid-19th century French political violence, to which she has lost both her husband and her son. And now for refuge she has been sent thither to Denmark by none other than Achille Papin, from whom she bears a tender and thoughtful letter of reference. And she joins the quiet and solitude of that landscape, staying in the sisters’ attic and preparing simple (but now very appetizing) meals for the infirm in the tiny village.

And again decades pass, all in the quiet repetition of sameness, till one day Babette the refugee cook learns that she has won a French lottery jackpot of 10,000 francs (a friend has annually purchased a ticket for her). With her new-found wealth she asks if she can prepare a meal for the sisters and their flock to celebrate the centenary of the founder. And then, surprise, the fireworks begin to soar and flame. Babette ventures to the nearest city to find necessary ingredients as the sisters to their horror begin to suspect that this “meal” will be more than tea and crackers, a fear that amplifies when cases of wine arrive. And the meal is a feast indeed, sumptuous, with finest china and cutlery and elaborate courses of exquisite food and wine. The guests’ resolve to not enjoy the repast, comically passing off its splendors as if they dined on such fare every day.

In this case, though, the truth will out, thanks to the reappearance of the long-absent Löwenhielm (Jarl Kulle), now an esteemed General, who is again visiting the same ancient aunt, a wealthy spinster, who lives nearby. And it is only the mysterious, unforeseeable reappearance of Löwenhielm that explains the mystery of the present feast, he having decades before consumed the same miraculous menu at the celebrated Café Anglais, whose female chef was the toast of Paris. This present convergence radically affects lives of five people: sisters, suitors, and, of course, Babette, for she has spent the whole of lottery prize on one dinner for twelve.

Nothing is, so to speak, fixed or set aright, at least in the conventional plot turns that we might think of as “happy endings.” Rather, the feast affords to all guests a profound understanding of the contours and meanings of their own lives. And the same can be said for the reconciliations that delight in the feast has instigated in the aging “flock.” Indeed, strangely, in the closing words of T. S. Eliot’s Four Quartets, the scene catches and inspires the hope that “all shall be well, and all manner of things shall be well…” For them all, in terms too complex to explain here, understanding, content, and wholeness have arrived, though nothing on the surfaces of their lives has changed.

The big question that follows upon this at once profoundly strange but deeply satisfying convergence of lives is from whence it originates. Is this all fortuitous chance, or perhaps design hidden within seeming randomness by some transcendent Other? For most of the tale, it seems that the acute theological observation of the south Chicago Dutch Reformed immigrant settlers is more than apt: “Love God, but don’t put anything past Him” (Peter De Vries, The Blood of the Lamb, 1961). For all their immeasurable faith, the devout and good get kicked around a lot, and often horribly so. There is, though, another approach to these somber realities, one akin to the sort suggested by Babette’s Feast. In Thornton Wilder’s award-winning epic novel, The Eighth Day (1967), central characters ponder the baffling tragic mysteries that befall their own good and noble lives. At one point the bewildered son of a man sentenced to execution after a mistaken conviction seeks the counsel of a nearby Native American sage. In response to a host of “why” questions, the wise fellow asks the boy to look at an intricately patterned rug on the floor, and he then asks him to turn it over, exposing an underside that seemingly has no pattern but countless loose ends jaggled together. Yet, it is the same rug, to be sure, and if it still retains even a semblance of pattern, it is but faintly evident. Or, is all we can know of Providence, simply Paul’s assurance to the besieged Roman Christians, that nothing can remove them from the love of God no matter what devours them?

Sign Up for Our Newsletter!

Insights on preaching and sermon ideas, straight to your inbox. Delivered Weekly!

Categorized into Providence

Babette’s Feast (1987) – 3