Decalogue I (1989). Written by Krzysztof Kieslowski and Krzysztof Piesiewicz. Directed by Kryszstof Kieslowski. Cinematography by Wieslaw Zdort. Music by Zbigniew Preisner. Starring Henryk Baranowski , Maja Komorowska, and Wojciech Klata. Facets Edition. Rating: G, 56 mins. Rotten Tomatoes: 100%.

In the late 1980s in Poland, two fellows put together what is generally recognized as one of cinema’s greatest accomplishments, namely Dekalog (1988-89), a ten-part series for Polish television on the Ten Commandments. Krzysztof Piesiewicz and Krzysztof Kieslowski did the writing, and the latter did the directing. Due to licensing difficulties they were, remarkably, not readily available in the United States for over a decade, finally appearing in 2003 in a DVD edition from Facets. They now appear in a definitive edition from the Criterion Collection.

Kieslowski and his co-writer, Krzysztof Piesiewicz, a Polish lawyer for Solidarity and later a post-communist senator, started the project as a kind of defiance. After their film No End (1987) was panned by all their major constituencies–the Roman Catholic Church, the Communist Party, and Solidarity, the militant anti-communist labor union, Piesiewicz joked that they should make a film on a nice, safe topic, such as the Ten Commandments, just so no one could possibly object. Before long the taunt turned into project. The two were going to write the screenplays, and each would get a different director, a plan from which Kieslowski, having liked them all, later retreated, choosing instead to direct all of them but to use a different cinematographer for each so all would have a different visual style.

Dekalog as a whole focuses on the residents of a housing complex in post-Communist Poland, whose lives become subtly intertwined as they face emotional dilemmas that are at once deeply personal and universally human. Using the Ten Commandments for thematic inspiration and an overarching structure, Dekalog’s ten hour-long films deftly grapple with complex moral and existential questions concerning life, death, love, hate, truth, and the passage of time. They are not doctrinaire religiously, to say the least. Nor is it entirely clear which commandment several of the films attend to, especially since Roman Catholicism’s order differs from the usual Protestant ordering.

Decalogue I is not a mild tale, though it is entirely lacking in sex, violence, or blasphemy, all those things that trouble many viewers, and rightly so, given the immense gratuitous crassness that characterizes so very many Hollywood films. Not so here, though the subject matter is more than harrowing and readily haunting. And it is made the more so by the film’s precise and delicate sensitivity, both emotional and religious, on what is perhaps the hardest topic of all. A middle-aged father and cybernetics professor cherishes his young son, and the two have a close bond of affection and respect, especially since the boy’s mother works abroad for long periods of time. At the time of the film, the boy’s chief female support is his aunt, a kindly and devoted Roman Catholic who encourages the boy’s religious questions and the taking of religious instruction, something his scientist father respectfully allows but personally disdains. In a patient, well-constructed scene, Irena explains to Pavel that in the love of one person for another, amid and through the material, we glimpse what God is like and sense divine presence. The crisis in the film slowly emerges as the father encourages his son’s use of the computer to determine if the water on a nearby pond will freeze sufficiently to allow skating. The computer says it will, but not quite trusting its analysis, the father himself walks the pond late at night. When the next afternoon the boy does not return home, the father searches desperately for his son, only to end up at the pond where two skating boys have fallen through the ice.

The film deepens its mounting thematic in depicting the nascent capacities of the computer as assuming virtual godlike qualities, such as presence, power, faithfulness, and even a kind of personalism. Indeed, it would be more than easy to extend trust to it as an all-knowing, almost magical entity worthy of human trust. Indeed, the film seems prophetic, given humankind’s recent devotion to the magic and powers of phones and damsels Siri and, even more so, Alexa, whom one now instructs to turn lights on and off and start the car. “I am the Lord thy God; thou shalt have no other God but me.” Really?

A second conspicuous, and amply mysterious device is the insertion on the periphery of the tale the presence of an unspeaking figure who simply watches, and watches, sitting by an outdoor fire amid the winter cold.

He does not speak or motion but only watches, attentive but detached, here a kind of alternative presence to the computer, looming over events, providing a frame or at least a silent interpreter or presence of some sort. The camera watches him as he watches back; he appears in eight of the ten films in Dekalog. He seems to loom over the events, providing a frame or at least a silent interpreter or presence of some sort. If the computer raises one sort of question about the modern character, or imposture, of the divine, a usurpation of qualities historically ascribed to the Holy, the pond-side figure echoes the modern notion of a present but absent God, remote and uncaring. These may provide atmospherics, but it is more than likely that something more is afoot than incidental mood-making. And it is in this context, then, we see a day in the life of a loving trio of father and son and aunt.

So the worst thing that can happen does—to both Pawel and his family. What was not supposed to happen, according to advanced scientific prognostication, does happen.

The father of the boy, Kryszstof, whose name might be more than a little ironic, given the first names of the film’s writers and trusts his math and his computer to predict the thickness of the ice. And good man and loving father that he is, he himself when Pawel is asleep goes out to walk the ice to make sure of its strength. And still, well, and still, bad things happen to the innocent and the good and loving, no matter how much care people take. Evil smiles, and strikes whom it will, and the toll simply eviscerates those left behind. This urgent question about the goodness of God is dead-central in the film, the drowning death of young Pawel, an eager, charming, and smart child, and a victim of over-confidence (faith?) in science and technological innovation. The conclusion only amplifies such questions.

The last scenes in the film finds Pawel’s father making his way to the interior of a large, unfinished, and dimly lit open-air cathedral, the same we’ve already seen in daylight from a distance.

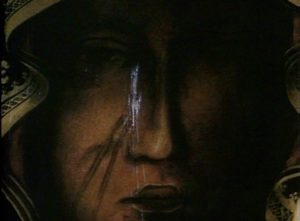

Krzysztof enters from the rear, faint light from the exterior barely silhouetting his distant form. The camera shifts to his point of view to see a makeshift, candle-lit altar (a long, thick board resting on piled blocks); above and behind hangs on scaffolding a large color portrait of the Virgin and Child, candles burning below and above the portrait.

Kryszstof proceeds to overturn the altar, toppling boards, bricks, and candles. The camera then cuts to the simple, iconesque Virgin, holding her own Child, who will in the fullness of time suffer agonizing murder. And now in the present, though, what seems to be tear after tear drips down her face. These, of course, could be coincidental drips of wax from the candles arrayed along the length of the plank above and mean nothing at all.

Or they could be something else, though still wholly natural–an emblem of wordless assurance of the miraculous presence amid life of Divine Compassion, an image prepared for by the aunt’s explanation of God to Pavel.

That father Kryszstof, whose name derives from Jesus himself, might find solace there seems improbable. Afterward, however, in an equally surprising move he moves from the remnants of the table to the baptismal fount, and there he removes from the fount the icy block of water to press it to his sweating forehead. To what end, or what such a gesture might suggest or symbolize, well, go figure.

Sign Up for Our Newsletter!

Insights on preaching and sermon ideas, straight to your inbox. Delivered Weekly!

Categorized into 1st Commandment, God, Suffering

Decalogue 1 (1989) – 2