Home » Sermons » Written Sermons »

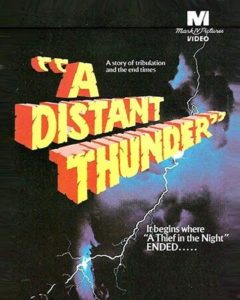

When I was in high school, I accompanied a friend to a youth group New Year’s Eve party at a local Pentecostal church. Mostly the party was what you would expect: lots of goodies to eat, pop to drink, games to play. But at one point in the evening all of us were gathered in the church’s sanctuary to watch a movie. What we saw, however, was most certainly not a Disney production. The movie was called A Distant Thunder, and not to put too fine a point on it, the film frankly scared me half to death. Basically the movie follows the lives of several college-age kids following the rapture.

In classic dispensationalist, pre-millennial style, the movie suggested that at some point Christians will disappear from this earth and a period of tribulation will follow during which everyone will be required to receive a mark on the hand or forehead. In this movie, those who refused this secular branding were threatened with some ominous, though unspecified, punishment. The heroes of the film did not escape via the rapture the first time because they had been only ho-hum Christians before. But now having seen their true Christian friends disappear, their faith returned in a big way.

The movie ends when a few of these Christian youth who refused the mark are arrested and herded into a kind of prison courtyard somewhere. And try though I may, I will never forget the film’s concluding image: one of the arrested Christian youths looks up just in time to see the steely glint of a guillotine blade whistling downward to decapitate one of her friends!

All in all and ever since then, I much prefer to watch the ball drop in Times Square on New Year’s Eve! But many of us know that the kind of scare-tactic scenario shown in that film is pretty common in some parts of the wider church. And although theologically speaking some of this seems to be from way out in left field, we should admit that the Bible itself provides plenty of grist for apocalyptic mills (or grist for “pre-mills” in this case). Our passage today from Luke 21 is a classic and good example. Within the span of only a few verses Jesus manages to throw in all manner of frightening, unsettling, almost bizarre imagery ranging from astronomical portents in the heavens to the raging of oceans here on this planet. In the first 24 verses of Luke 21 (that we did not read this morning), there are even more predictions of wars, earthquakes, and global mayhem of all kinds.

So although we Reformed folks have our reasons for disagreeing with most of the apocalyptic schemes that have been developed in history, we cannot deny that very often it is no one less than our Lord himself who contributes to some of that. Let’s look at Luke 21 and in so doing try to answer a couple of questions. First, how should we understand a passage like this one? Second, why does church tradition always begin the Season of Advent with dark passages like Luke 21? In Matthew, Mark, and Luke, just prior to his arrest and crucifixion, Jesus delivers apocalyptic sermons like the one before us this morning. Church tradition always begins Advent here. But why do we initiate that time of the year that celebrates Jesus’ birth by focusing on a passage that comes just prior to his death? In short, how and why is Luke 21 a good way to begin Advent?

To answer these questions we start with the passage itself. As is typical of basically all of the Bible’s eschatological or “last things” passages, Jesus in Luke 21 quite freely mixes up words about events that will take place very shortly with words that seem to point much, much further into the future. In the first 24 verses of this chapter, Jesus speaks about not only wars and rumors of war in the distant future but also, more narrowly, he talks about the fall of Jerusalem, which would take place about forty years after the sermon recorded in Luke 21. Similarly in other verses, on the one hand Jesus seems to be pointing forward to his own death and resurrection (which would happen within a week’s time) yet on the other hand he talks about what looks to be the very end of the world as we know it. Sometimes Jesus talks about next week. Sometimes he talks about something that could come a thousand years later.

It’s all jumbled together, however. If Jesus was trying to draw up a neat and tidy timeline that we could turn into an eschatological chart and then hang on a bulletin board somewhere, he didn’t do a very good job of it. But that’s because he wasn’t drawing a chart. That has not prevented many people from drawing charts of their own anyway. Although he died almost two years ago now, for many years one of the oddest birds on religious cable television was Jack Van Impe (and his Maybelline wife with the curious name of Rexella). If you ever dipped into his show, then you know that the standard format is to give a rundown of daily news events, especially anything connected with the Middle East. Mr. Van Impe then comments on that news story and buries the viewer under a fusillade barrage of biblical texts from Ezekiel, Daniel, Revelation, and gospel texts like Luke 21. Each and every news story is said to be a clear fulfillment of this or that biblical prophecy.

But even the casual viewer of the show knows that over time the same passages have gotten applied to dozens, maybe hundreds, of different events. One year Afghanistan is a clear fulfillment of this and that text from Ezekiel and so this was a sign the world would end any moment now. But then the world didn’t end, and so a year later yet another event got tied to that same passage (and you get the feeling that maybe next month yet another event will be treated the same way based on the same text).

It’s all very strange. But it’s not as though we Reformed folks don’t believe prophecies are fulfilled. It’s just that we don’t make the definition of fulfillment quite so narrow. With the exception of Jesus’ second coming, we don’t look at the various predictions Jesus made here and then insist that each one is allowed to be fulfilled one and only one time in history. Jesus wasn’t giving us a countdown checklist of items to tick off one at a time as they happen. Instead prophecy is more open-ended and we look for multiple horizons of fulfillment. Some of the things Jesus talks about here have happened many times in history already and may repeat themselves many times in the future, too. There will be lots of mini-apocalypses, lots of times that will fit the descriptions given in Luke 21.

But in Luke 21 Jesus is doing more than telling us that history will be rough. He is also trying to reassure us. Jesus wants us to know that despite wars, earthquakes, and disasters of all kinds, this world still belongs to God. None of those dreadful happenings need make us conclude that the gospel is false or that Jesus is not Lord after all. God still holds history in his hands, broken a history though it often is. And what’s more, all appearances to the contrary, the whole thing is heading the right direction. Even in verses 27-28 when Jesus describes terrifying cosmic events involving the moon and the stars, even then he tells the disciples that believers can hold their heads up high and rejoice. Nothing must shake our faith-given resolve that God is in charge and so Jesus is coming again.

Because as he goes on to say in verses 34-36, if the news headlines are all you have to go on any given day, you will almost certainly despair at times. Pour another cocktail, throw up your hands, sit in some corner of your den and watch the TV screen flicker with images of terrorism and rampaging violence everywhere. If that’s all you can do most days, then like lots of other folks in society, you will find it easy to conclude that the whole world is going to hell in a handbasket. So long as you think that the shape of the future, and the securing of some kind of globally good outcome, are up to human beings alone, there will be no end to the excuses you could find to crumple up into a little ball of utter hopelessness.

Jesus says don’t do that. Don’t think it’s up to you or any government anywhere on earth. What secures the future, what gives us a future despite the multiple threats to our very existence that surround us all the day long, is no less than the promises of God through Christ Jesus the Lord. If you despair and become too wrapped up in how bad things are for now, then the day of the Lord may close on you like a trap, Jesus says. But if you keep faith in Jesus, then not only will you find a motivation to keep on moving forward despite this present darkness, you will also eagerly await the Son of Man’s return and will know that you will stand firm right next to that cosmic Lord when he does finally show up.

The movie I mentioned in my opening this morning attempts to frighten people into becoming Christians. That, however, was not Jesus’ method. Jesus sought to comfort us, to show us why we need not be made afraid. Nothing that happens now, and nothing that may happen when the end truly is near, will alter the unshakeable fact that in his death, resurrection, and ascension, Jesus won a cosmic victory over evil that will never he undone. Maybe this is why our passage’s concluding verses this morning tell us that the crowds eagerly soaked up Jesus’ teachings day after day. If Jesus had been a doom-and-gloom naysayer and fear mongerer, you sense that people would have stayed away. It was Jesus’ confident hope of glory that drew them in.

It should be the same for us today as well. And never should that be more true than as we begin this Advent Season. But earlier I said that the second of two questions we need to tackle this morning is how and why apocalyptic passages like this one serve as good beginnings for Advent. As we have noted together in also past years, there most certainly is nothing very “Christmasy” in a text such as Luke 21. About the only time such imagery is associated with the holiday season is when someone is trying to be funny or off-beat.

Some years ago comedian Bill Murray starred in a movie that was one of the many, many take-offs from Charles Dickens’ story A Christmas Carol. Murray was the Scrooge figure in the film as he played a hard-nosed television executive who disliked everything about Christmas except for the fact that his TV network could make a lot of money off the holidays. In the story this executive was producing a high-tech, whiz-bang, jazzed-up Christmas special to be aired on Christmas Eve. To get people’s attention, he promoted the upcoming special with an advertisement that was so frightening, it left his board of directors shaking in their seats after they previewed it. The ad featured startling images of nuclear holocaust, drive-by shootings, terrorist bombings, and meteors striking the earth. The ad’s tag line was something to the effect, “In a world as downright terrifying as this one, now more than ever you need to see this year’s Christmas Eve Spectacular right here on NBC. Don’t miss it–your life might just depend on it!” You can watch it here.

Well, of course, everyone hated the advertisement because for one thing it was so completely at odds with the holiday spirit and for another thing it would frighten children. But of course in this movie this was supposed to be comedy. We laugh at a Scrooge-like person who is so out to lunch that he actually would associate images of atomic bombs with Christmas! Only a mean-spirited person would link the violence of this world with the very holiday season that is supposed to make us forget about our troubles for a while.

Ironically, however, the kind of imagery that most people would deem out-of-place at Christmastime is precisely the imagery the church has long insisted must be placed at the very head of the Advent Season. In a way, we could take that same sequence of scary video footage used in the Bill Murray movie and show it not as the reason why you need to watch some silly TV show but as the reason why every last one of us needs the Son of God whose incarnation makes up the very center of Christmas. I need not tell you, probably, that in that movie, once Bill Murrary’s Scrooge gets converted to the supposedly “true” Christmas spirit, he would never again think to connect Christmas to holocaust. But that’s just the problem with what most of our society thinks Christmas is about.

We begin Advent with passages that teeter on the edge of Jesus’ death because we live in a world that does terrible things like crucify the Son of God. Ours is a world of upheaval, of genocide, of pride, selfishness, greed, and violent acts perpetrated on the innocent and the unsuspecting. Soon our neighborhoods will look so pretty as they get decked out with lots of Christmas lights. And if the world looked just that pretty and serene most of the time, then this world would need no Savior. Soon we will start to hear secular holiday songs that convey trite sentiments along the lines of, “Well by golly have a holly, jolly Christmas this year.” If ditties like that could cure what truly ails us in this life,, then there never would have been any need for God’s Son to go through the bloody trouble of coming here in person.

And perhaps as we enter the second Advent and Christmas Season during a global pandemic that will not quit, maybe it is a little easier to convince people of all this and of why we begin Advent with an apocalyptic text.

Advent begins with a frank, honest assessment of history’s perils, of the present moment’s terrors, and of the future’s all-but certain calamities because looking all of that square in the face is the only way to frame Advent and Christmas correctly. We would not even need Advent if the apocalyptic features to life mentioned in Luke 21 were not our reality. So let me suggest that we all try a little exercise these next four weeks. No, I’m not going to suggest that we dispense with holding or attending holiday parties. And I’m not going to suggest we skip buying Christmas trees or decking out the shrubbery with lights. Nor will I suggest we dispense with giving gifts to our precious children.

But what I will suggest is this: when you sit in the soft glow of your Christmas tree’s lights sipping eggnog some evening after dinner; when you see the twinkling of your neighbor’s yard decorations or see the shimmering of your child’s eyes as she opens a gift; when you enjoy the delicious food and good drinks of someone’s holiday party, then at some point say to yourself that this is not a distraction from the brutality of real life. All this holiday ambiance is not a chance to forget the world’s troubles for a little while.

Instead see in those pockets of light and joy nothing less than the only bright hope this troubled world has. Remind yourself that the darkness still swirls all around but precisely because that is so, and not despite it, we must recall that a light shines in the darkness–a light no darkness, no apocalypse, no warfare, no falling of meteors, and no holocaust can prevent from shining. Let your holiday lights shine this season. But never forget Whose light it finally is and why this raw world so badly needs to see it. Amen.

Dive Deeper

Spark Inspiration:

Sign Up for Our Newsletter!

Insights on preaching and sermon ideas, straight to your inbox. Delivered Weekly!

Written Sermon

Luke 21:28-38: At That Time – Advent 1C