Our prayer life should be our autobiography, C.S. Lewis once observed. But that is also why Lewis thought the Hebrew Psalter was such a fitting prayer book since it contains prayers that fit a wide variety of life’s experiences. Were the 150 Psalms all in one particular emotional register, what help would it be for all the other seasons of our lives that do not always fit into that one category or emotion? If we are to use the Psalms as our prayer book, then they need to be exactly what they turn out to be: widely varied.

About one-third of the 150 Psalms are Lament Psalms, and Lord knows we need those on a semi-regular basis in our lives. But Psalm 138 counts as very nearly the anti-Lament Psalm. This is a song and a prayer that is singularly hopeful, upbeat, confident. God is praised without reservation from first to last even as everyone else—even the kings of the earth—are encouraged to join the choir. The psalmist is certain that God has taken care of him in the past and is utterly confident this will continue to happen in the future (although the psalmist is not averse to the plucky closing line more or less commanding that God make sure that this protection will be extended into that future too!).

It is a testament to the honesty of the Hebrew Psalter that it can contain both Lament Psalms that question God’s faithfulness in one’s life AND Psalms like this one that recognize how faithful God just generally is. And what if it turned out that some of the same poets wrote both Psalms of Lament and Psalms of Praise like Psalm 138? It seems likely that this is the case, and that is something we can all relate to. Even the most exuberant Christian can get knocked sideways, can be led to question the very things that in other seasons of her life led her to shout and sing triumphantly in worship services. Faith does not require that we feel the same way about everything every day and all the time. There is something lovely and comforting about that.

Of course, preachers and worship planners are more at ease with the high notes of praise such as we find in Psalm 138. But it seems to me we should never preach on a Psalm like this without at least a brief acknowledgement that on any given Sunday, not everyone out there in the pews (or in the seats) is “there.” We should never preach the Psalms of exuberant confidence and praise without remembering—and perhaps overtly reminding the congregation—that all those other Psalms are out there too as testament to the fact that even faithful believers can pass through very different seasons.

Still, focusing on the beauty and confidence of our faith—and on the need to praise God over and over for God’s goodness and grace—is a fine thing to do on a regular basis in worship and also in our preaching. And in the case of Psalm 138 that is particularly poignant thing to do because of what the psalmist notes in verse 6: the real glory of Israel’s God is not only almighty and awesome power or the ability to do majestic cosmic miracles and splendors. No, the glory of Israel’s God—the source of the chesed or lovingkindness for which the Psalter most consistently praises God—is God’s ability to stoop low to take notice of the poor, the marginalized, the people who are all-too-often invisible to even our human eyes. It is the Lofty One’s attention to the lowly ones that truly startles. All “gods” (as they are referred to in verse 1) are said to be majestic and awesome and fearsome. The Babylonian and Phoenician and Egyptian (and later the Greek and the Roman) gods and goddesses all had that. But as often as not that power rode roughshod over us mere mortals who were but pawns in a larger divine drama. “As flies to wanton boys are we to the gods” the old line has it. “They kill us for their sport.”

But not Yahweh. Not the God of Israel. This God’s glory is precisely in God’s care for the weak, in this God’s desire to work with little folks like Abram and Sarai, like Moses, like David. Small wonder that when this God eventually comes to this planet in person, it is in the person of a poor carpenter’s son from the backwaters of the Roman Empire whose origin story takes place not in a palace but in an animal lodging. This is the core characteristic of God that launched The Magnificat of Mary in Luke 1: even as God had somehow found favor with little-old-nobody-from-Nazareth Mary, so Mary foresaw that God was going to continue to do this, scattering the proud and rich and haughty so as to elevate folks like her.

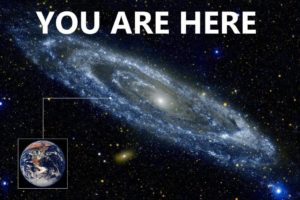

This wonder at God’s ability to notice us in all our littleness is a good focus for also today. In fact, considering how much more we now know about the vastness of the universe—and how not a few people use this as a reason to dismiss the idea that life on planet Earth could possibly matter—it is important to recall that God’s truest grandeur has always been his stooping low to notice, love, and care for each one of us. Yes, the world, the cosmos, is grand and we are occupying the tiniest speck of universal real estate. And yes, the day may come when we confirm what many suspect: that there are other inhabited worlds out there. Some, including in the church, will see this as a diminishing of our status. Gone will be the days when human beings consider themselves unique in the universe, the pinnacle of all possible sentient created beings. But if we can maintain the wonder that animates Psalm 138, then we need not feel threatened by such a prospect any more than we should buy the idea that the cosmos is too big for us to count as anything other than a universal footnote.

After all, a major part of God’s “bigness” to Israel was precisely his ability to see and celebrate “littleness.” And that feature to God has not changed. Indeed, in Christ Jesus we see exactly how good God is at getting very, very specific!

Illustration Idea

In his “Space Trilogy” of science fiction novels, C.S. Lewis toyed with the idea of intelligent life on other planets. Unlike “Star Trek” Lewis did not do so by zooming far out into outer space to find worlds like Vulcan but instead imagined other life right here in our own solar system, on Venus perhaps or Mars. In his stories, though, Lewis does not let this idea of other lifeforms diminish the Gospel. Instead he lets Earth retain its unique status as being “The Visited Planet,” referring to this being the world where the Son of God became incarnate. Beings from other worlds would speak of Earth in hushed, almost reverent tones for this very reason. There may be life on other planets, Lewis was essentially saying, but that will never remove us from God’s loving care or from the fact that once upon a time, God came down here quite literally in person to get saving work done!

Sign Up for Our Newsletter!

Insights on preaching and sermon ideas, straight to your inbox. Delivered Weekly!

Sermon Commentary for Sunday, February 10, 2019

Psalm 138 Commentary