Taking his cue from the setting given to us in verses 1-3, Justo González says these parables are less for the lost than they are for the “never lost”—those who foolishly think they have no need for the Physician of heaven.

Our lectionary passage starts with the grumbling Pharisees. What are they grumbling about? Jesus is welcoming in tax collectors and sinners, opening the door for them to become part of the community. But these folks are not the kind that should be “in”—they are sinners, and in the case of the tax collectors, very likely Gentiles. The Pharisees grumble because their presence makes the meal unclean, and for people concerned with ritual cleanliness, this is annoying!

But for their part, the tax collectors and sinners are said to have come to listen to Jesus; they are on the road to repentance, which is a possibility completely lost on the grumbling Pharisees. So, Jesus tells them three stories, though he says he is telling one story (the word parable is in the singular) about their attitude/blindspot in light of the character of God.

Separating these stories from the third in the parable set (the Prodigal Son) helps us see things we might have missed. Understandably, that third story is the climax of Jesus’ message. But, there is a lot that is underscored in the story of the lost sheep and the lost coin—some of which we don’t get in the lost sons story.

For instance, one of themes of Luke’s gospel is the way stories are paired. We often find Jesus interacting with a man and then a woman, of using examples from the lives of the rich and the poor, and these stories in Luke 15 are no exception. As Kenneth Bailey points out, this isn’t just a Lukan convention, it is from God, seen in the life, values, and ministry of Jesus’ time on earth. They are not just effective storytelling techniques, they are the implicit expression of the very values of God towards God’s people: equality, inclusion, no hierarchy of accessibility… So here we have the story of a rich male shepherd (100 sheep is a big flock), and a poor woman (the ten coins she has saved is about a week and half’s worth of pay). Jesus identifies himself with both the man and the woman and uses their actions to show what God is like.

The lost sheep and lost coin stories also shape a picture of what God is like in a way that adds to the fullness of the depiction of the Father in the Prodigal Son story. There, the Father eagerly waits (and we assume intercedes for his son through prayer), ready to receive his son who was lost while carrying on with his work and responsibilities. But here, the shepherd leaves the 99 to look for the 1, and the woman goes to great lengths to find the coin that is lost.

As Kenneth Bailey outlines, through the first two stories, Jesus is telling a story about atonement (The Cross and the Prodigal: Luke 15 Through the Eyes of Middle Eastern Peasants):

- God accepts responsibility for the loss.

- God searches without counting the cost.

- God rejoices in the burden of restoration.

- God rejoices with the community at the success of restoration.

God accepts responsibility for the loss. The shepherd has lost one of his flock; even if “it was lost to him” (as he describes it to his neighbours), he knows that he is the one responsible for finding it. Jesus describes the sheep as “lost” using the perfect tense: it got lost and that “lostness” is still having an impact into its present. The lost sheep cannot “unlost” itself, just like the lost coin cannot find itself. For both to be found, effort must be exerted by another. God, out of great love for us, commits to the restoration of the lost.

God searches without counting the cost. Having committed to the search and rescue, Jesus shows us that God does so even at great cost. Though it is likely that the 99 sheep are in relative safety when they are left by the shepherd who is searching for the lost one, the shepherd still leaves the bulk of his wealth in order to get back a measly 1% of what belongs to him—well within the error margin of doing business. And the woman spends resources, time and energy, lighting lamps and sweeping her home as she searches carefully to find the lost coin. So too, Jesus does not seem to count the cost to himself as he willingly endures suffering and death.

God rejoices in the burden of restoration. Just as Jesus was glad to welcome and eat with tax collectors and sinners because they had come seeking him and were on the road that might lead them to repentance, the shepherd and the woman both celebrate at achieving the ends of their search and rescue missions. Notice how the stories describe restoration: the burden of our restoration lies in God finding us. Bailey provides beautiful nuance to the work of repentance: repentance is our “acceptance of being found” by the Holy Spirit in our lostness. The Holy Spirit carries us home to Christ’s heart in heaven where we are covered by his righteousness, and we learn to follow and emulate a new way.

God rejoices with the community at the success of restoration. The party of heaven could be the party on earth, if we accept the invitation. Or perhaps more fitting to the stories, the party of heaven could be our party on earth if we accept that Jesus has found us who are lost in our own religious priorities, opinions and views, and boundaries for who is in and who is out. Throughout our lectionary passages this summer, we have encountered Jesus repeatedly attempting to shake people loose from the boundaries of religious acceptability and ritual cleanness: who he says should be invited to the banquets, who and how he heals on the Sabbath and what he says to the church leaders who try to stop the joy from spreading… and more than once, we have seen how some of the people react; they do not want a party, they do not want to celebrate what was lost being found again, because the “rules” have been broken and that’s not fair!

I think this is the reason why Bailey describes restoration as a burden. Beyond the atoning work of Christ, we who are blind to our “lostness” become a burden to the restoration that others experience. We who are unable to accept the work of God in someone’s life because it does not match what we would have orchestrated for them, we become lost when we refuse the Spirit’s invitation to the restoration party, becoming another sheep or coin that needs to be found—rescued from ourselves.

When we refuse to celebrate what God has done, what God the Spirit is doing, we are estranged and “lost” when we could be at home, resting with the other sheep who know that the goodness and extravagant—perhaps reckless—care shown to one will be shown to all.

But here’s the good news. Like the lost coin, we may get ourselves lodged very deep into the cracks or crevices of the floor, but God who is like the woman who searches, will not stop until we are found and restored. Eventually, Lord willing, our repentance from our attitudes and exclusions, will become the reason for the celebrating.

Textual Point

In a number of his books that look at Luke 15, Bailey connects and interprets Jesus’ parable-trio with Psalm 23, and further ties the stories to sections of Jeremiah and Ezekiel. The parallel to Psalm 23 as the “story told” from the perspective of the lost sheep is quite lovely: having one’s soul restored when found, joining in the celebration of the table made in the presence of those who were once opposed to you, the gracious and loving work of the shepherd that undergirds the whole Psalm… If you’d like to read more, I’d suggest Bailey’s The Cross and the Prodigal.

Illustration Idea

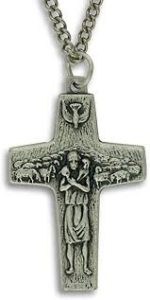

The pectoral cross that Pope Francis wears depicts the Good Shepherd carrying the lost sheep on his shoulders, with the whole flock following behind, and the Holy Spirit (depicted as a dove) hovering above at the top of the cross. It is said that the Pope chose to keep this cross (from his days as the Archbishop of Argentina) as a reminder of the call of the church as it follows Jesus and is led by the Holy Spirit: to seek out and welcome those in great need. We might even see the image of the flock following after Jesus as an image of our willingness to join the celebration.

Tags

Sermon Commentary for Sunday, September 11, 2022

Luke 15:1-10 Commentary